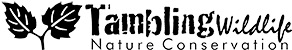

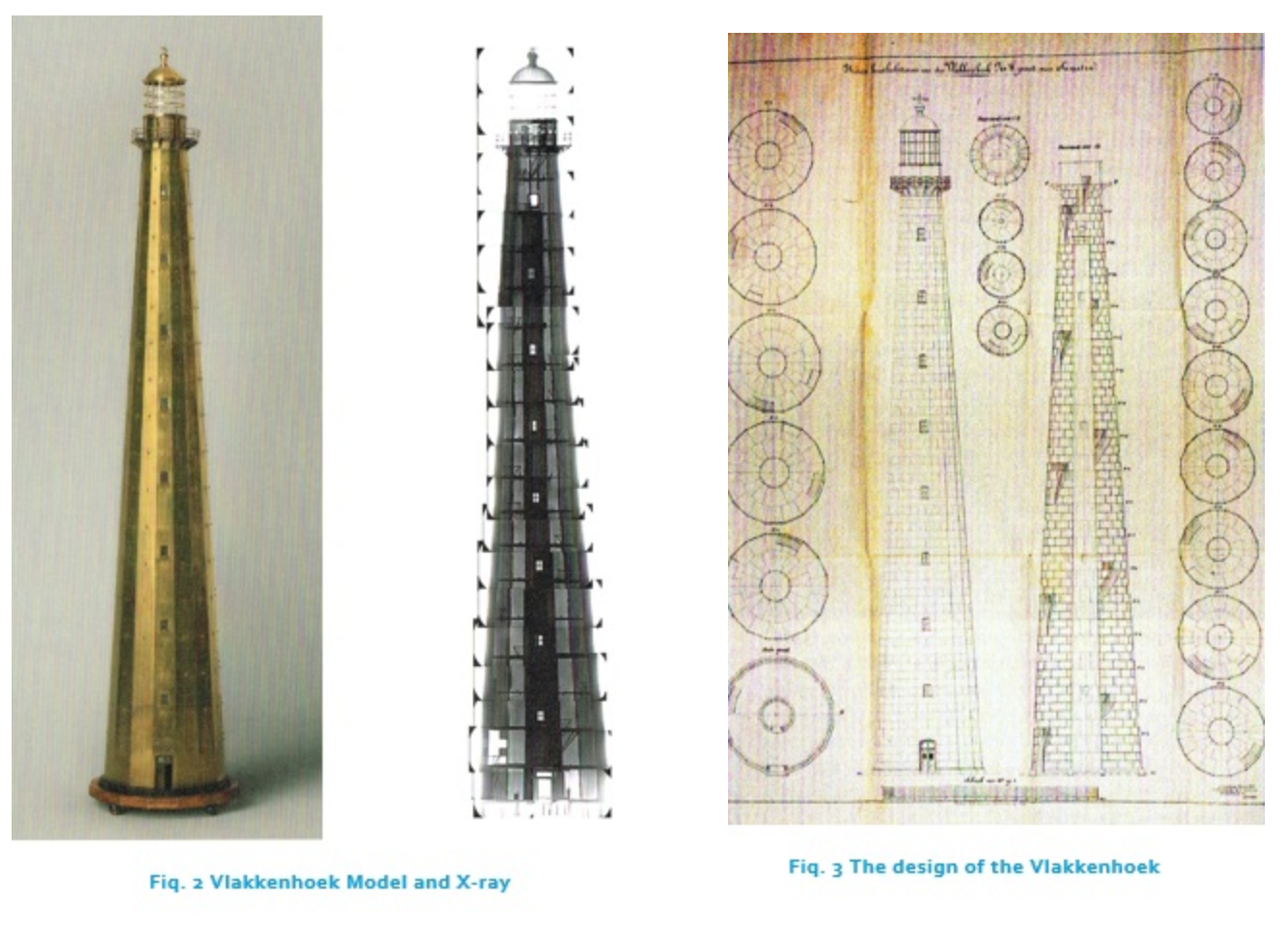

The paneled, sixteen-sided light-house was built in 1879 on the rugged outermost south-west tip of Sumatra, a place that in colonial time was known as Vlakkenhoek and is now called Tanjung Cukuhbalambing (Cukuh Belimbing).

At the time the Vlakkenhoek stood on the territory under the control of the King of the Netherlands, as indicates on the large plaques above the doors of all the lighthouse in the Dutch East Indies. The construction of the lighthouse was part of a long-term program aimed at building fifty coastal and harbor lights of varying size along the East Indies coast, in the Sunda Strait, along the north coast of Java, the straits of Madura, Bali and Bangka, and along important seaways in the East Indies archipelago.

MERCUSUAR

The light house – Mercusuar in Indonesia is still operational. This lighthouse marks the entrance to the Sunda Strait between Java and Sumatra one of the principal sea lanes in the Indonesian archipelago.

The lighthouse, corroded by the humid sea air at this strategic point in Indonesia, is an impressive example of the durability of the works carried out by engineer under colonial rule the Mercusuar was one of the tallest buildings in the East Indies archipelago.

BUILDING BY KIT

The Vlakkenhoek Lighthouse was built, as stated, in the spring of 1879. Labuan – Blimbing was the scene of un preceded activity as the technological invasion was conducted like an amphibian landing operation. The assignment was undertaken by the iron foundry Uzergieterij L.J. Enthoven & Co in The Haque for the sum of 53,975 guilders (the equivalent of half a million euros).

The whole procedure – the production (for which Enthoven was given eight months), transport and construction of the iron lighthouse – was not only documented but also part-tested in the Netherlands.

ERUPTION OF KRAKATOA

On the night of 27 August 1883, the small population was struck by a calamity of biblical proportion. The eruption of Krakatoa volcano, in the Sunda Strait, a mere 103 kilometers from Vlakkenhoek, devastated the iron routines that normally have ruled its existence.

The first eruption had already taken place in May. The extremely loud explosion and a ten-kilometer-high plume of steam and ash that followed must have filled the residents with terror. In the ensuing weeks, the ominous volcanic rumbling continued.

The main explosion began in afternoon of 26 August and lasted into early morning of 28 August. The eruption of the volcano was accompanied by a series of terrifying natural phenomena which seemed to herald the end of the world: sudden darkness, rains of ash and mud descending from the sky, a ‘flying’ cyclone, a series of seaquakes, thunder and lighting and other inexplicable electrical phenomena.

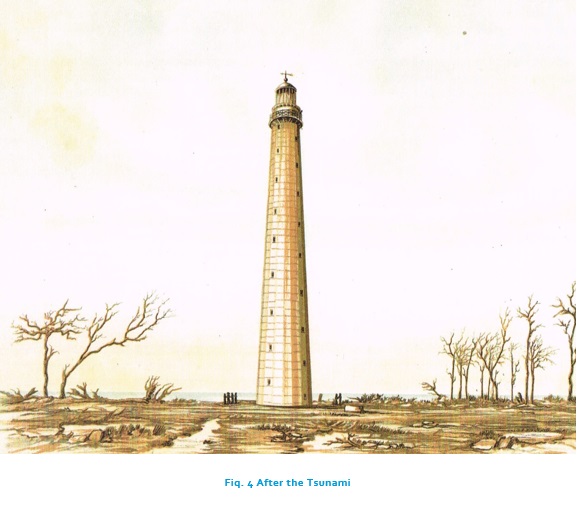

Towering waves suddenly appeared, leaving a trail of destruction in the coastal areas. More than thirty-six thousand people lost their lives in disaster with the coastal areas of Java and Sumatra to the west of the Sunda Straight being particularly hard hit.

The lighthouse compound at vlakkenhoek was not spared. Eyewitness R.A. Van Sandick, a Dutch engineer from the Department of Waterways, who visited the area by steamer a few days after the disaster, saw human bodies, piece of iron, uprooted trees, all entangled together a long way away from the settlements.

And the light house? It stood tall during immense chaos. A Large crack in the floor on the first story attested to the disaster, but more importantly the cotton mantle of the gas lamp was ruined and the glass chimney broken. As a result, the lamp could not be lit. Within three weeks of the eruption, the newspaper Sumatra Courant reported that an ancillary lamp had been placed in the lighthouse that be seen from two miles away.

Besides a symbol of superior construction technology, the Vlakkenhoek Lighthouse and all the other Dutch lighthouses, light beacon and harbor lights that were built between 1868 and 1897 to mark the East Indies coast and waters, were a symbol of power and domination.

They played a crucial role in Europe’s expansion into South East Asia as part of a network of colonial control over maritime domain. The state monopoly of the use of this kind of maritime technology – the optical ‘tools of empire’- enabled a small group of Europeans to establish its control over vast archipelago. The strategic importance attached to the maritime regions in securing that control around 1900.

Source: Indonesia and the Netherlands from 1600 by Harm Stevens. Page 66-81.